The Toyota Production System: The Blueprint That Changed the World

In the world of business management and manufacturing, few acronyms carry as much weight as TPS.

The Toyota Production System (TPS) is more than just a way to build cars. It is a philosophy, a culture, and a rigorous organizational framework that has revolutionized how the world thinks about efficiency.

While it originated on the factory floors of Japan, its principles (now often repackaged as “Lean“) power everything from software development startups in Silicon Valley to hospital emergency rooms in Europe.

But what exactly is TPS, and why does it remain the gold standard for operational excellence decades after its inception?

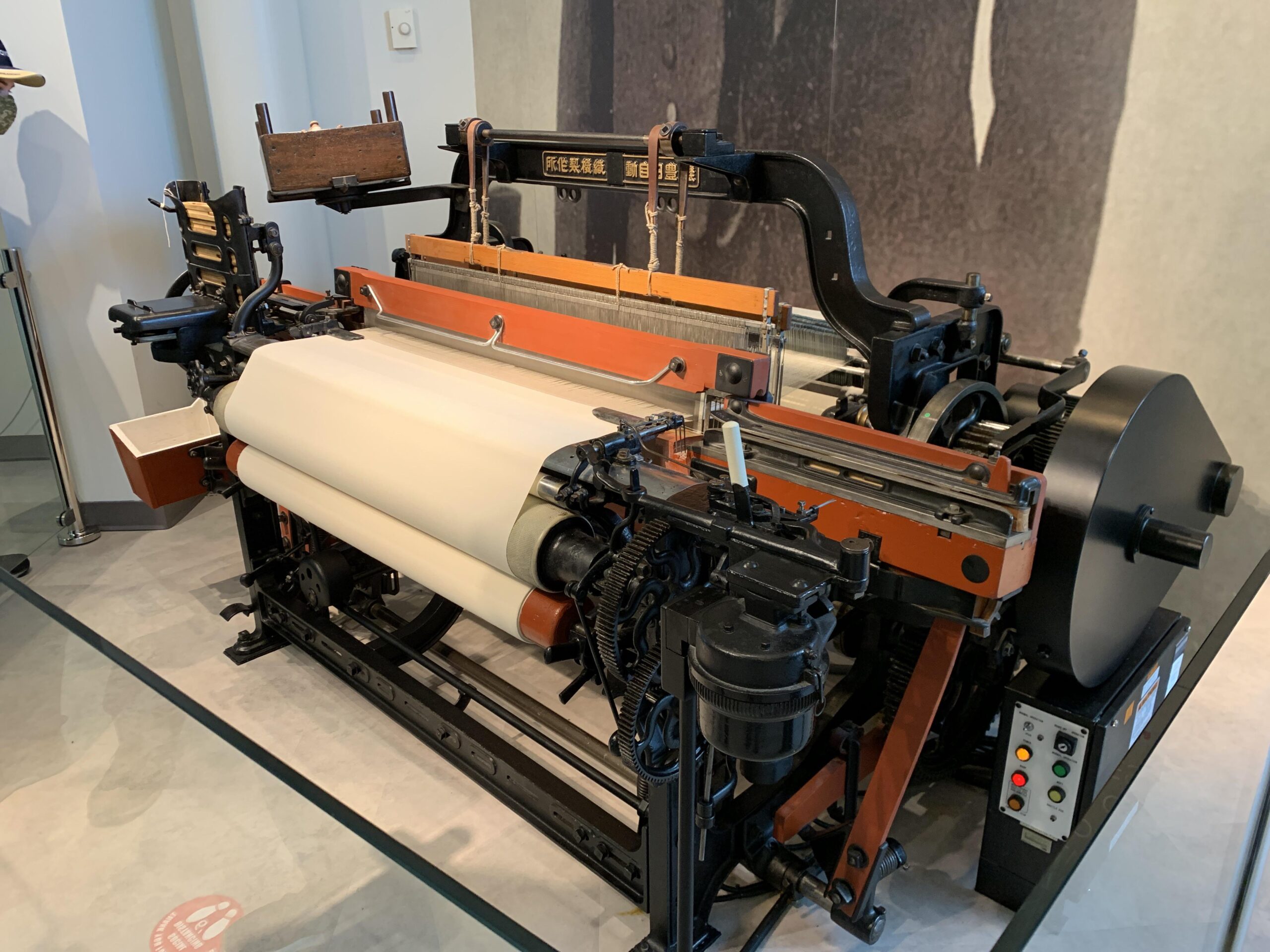

A Brief History: From Looms to Lexuses

The roots of TPS go back further than the automobile. Sakichi Toyoda, the founder of the Toyota Group, started with automatic looms. He invented a loom that would stop automatically if a thread broke. This prevented the machine from producing defective fabric and wasting material.

This concept (building “intelligence” into a machine) became one of the foundational blocks of TPS. Later, his son Kiichiro Toyoda and engineer Taiichi Ohno refined these ideas in the 1940s and 50s.

Facing resource scarcity in post-war Japan, they couldn’t afford the massive inventory buffers that American giants like Ford maintained. They had to be smarter, leaner, and faster.

The TPS “House”: Two Main Pillars

The Toyota Production System is often visualized as a house. The goal (the roof) is the highest quality, lowest cost, and shortest lead time. To hold that roof up, the house relies on two distinct pillars:

1. Just-in-Time (JIT)

“Making only what is needed, when it is needed, and in the amount needed.”

In a traditional “push” system, factories churn out products based on forecasts, often resulting in warehouses full of unsold inventory. JIT is a “pull” system. Production is triggered only when a customer places an order (or a downstream process signals a need).

- Continuous Flow: Moving products through the system without stagnation.

- Takt Time: The heartbeat of the line; matching production speed to customer demand.

- Pull System: Utilizing signals (Kanban) to request parts only when the previous ones are used.

2. Jidoka (Autonomation)

“Automation with a human touch.”

Jidoka is about built-in quality. It empowers any worker (or machine) to stop the entire production line the moment an abnormality is detected.

- Instead of fixing defects at the end of the line (which is expensive), TPS fixes them immediately.

- It separates the machine’s work from the human’s work, allowing one operator to manage multiple machines since they don’t need to watch them run—only fix them when they stop.

The Vocabulary of Efficiency

To truly understand TPS, you have to speak the language. Here are the core concepts that drive the system:

Kaizen (Continuous Improvement)

This is the heartbeat of Toyota. Kaizen assumes that no process is ever perfect. It encourages small, incremental changes initiated by the workers themselves, not just management. It turns every employee into a problem solver.

The 3 Ms of Waste

TPS aims to eliminate inefficiency, categorized into three types:

- Muda (Waste): Non-value-adding activities. The classic “Seven Wastes” include overproduction, waiting, transportation, processing, inventory, motion, and defects.

- Mura (Unevenness): Irregularity in the workload. A frantic rush followed by a lull creates inefficiency.

- Muri (Overburden): Pushing employees or equipment beyond their natural limits, leading to burnout and breakdowns.

Genchi Genbutsu (Go and See)

You cannot solve a problem from a desk. TPS requires managers to go to the Gemba (the actual place where work is done) to observe the process and understand the root cause of an issue.

Why TPS Matters for Your Business

You might not be manufacturing sedans, but the principles of TPS are universal.

- If you are in Software: The “Agile” and “Scrum” methodologies are direct descendants of TPS. JIT coding means you don’t build features nobody asked for.

- If you are in Healthcare: Hospitals use TPS to reduce patient waiting times and eliminate errors in medication dosage.

- If you are in Logistics: Amazon’s fulfillment centers are giant engines of JIT and waste reduction.

Conclusion

The Toyota Production System teaches us that efficiency isn’t about working harder; it’s about working smarter. It’s about respecting people enough to listen to their ideas and building processes that make excellence the path of least resistance.

Whether you are running a multinational corporation or organizing your personal workflow, asking yourself “Is this adding value?” or “Is this Muda?” is the first step toward world-class performance.